Caretakers of the Taj Mahal have been battling brownish discoloration of the icon's marble facade for decades. A new study has found burning municipal waste in the neighborhoods around the Taj contributes a significant amount of the organic matter that causes the discoloration. The same work also found the resulting air pollution contributes to more than 700 premature deaths in the area each year. The work comes from Armistead "Ted" Russell in the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Georgia Tech along with his colleagues at the University of Minnesota, Duke University, and the Indian Institute of Technology. It was published Oct. 7 in the journal Environmental Research Letters. (Photo: Michael Bergin) |

Researchers from the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering have found burning trash around the Taj Mahal is not only a major factor in the monument’s discoloration, it’s contributing to hundreds of premature deaths each year.

The new study, published Oct. 7 in the journal Environmental Research Letters, builds on previous work that led local communities to ban burning of cow dung cakes, a common cooking fuel.

Now, with support from the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Agency for International Development, scientists have quantified how much of the organic matter deposited on the Taj Mahal comes from burning municipal solid waste, and it’s 12.5 times greater than the particulate matter generated from the dung cakes.

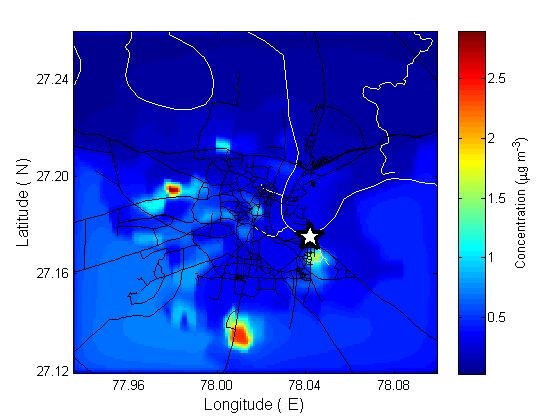

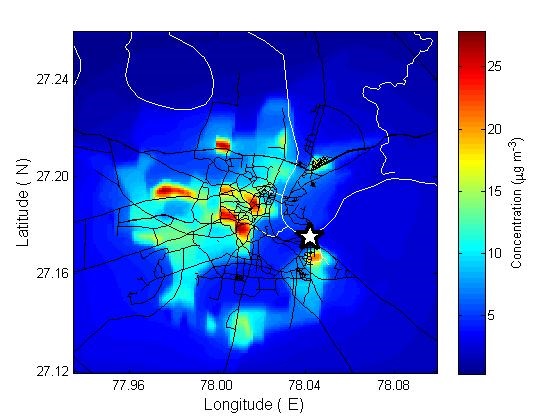

Graphics show the annual average concentration of fine particulate matter (often called PM2.5) that results from burning cow dung cakes, left, and municipal solid waste, right. The research team reported higher concentrations of the air pollution in poorer neighborhoods from burning both materials. The location of the Taj Mahal is indicated by the white star. (Illustration Courtesy: Armistead "Ted" Russell and Raj Lal.) |

"While the response to the initial work was to address dung cake burning, another — albeit now obvious — contributing factor was identified after doing some careful and novel additional field work and modeling analyses," Armistead “Ted” Russell told the journal’s sister website Environmental Research Web.

"We don't want our study to detract from the earlier focus on providing clean cooking fuels in Agra. We show that municipal burning is a larger contributor, but both municipal solid waste and dung cake burning for cooking are important when health and monument preservation are of interest," said Russell, the Howard T. Tellepsen Chair and Regents Professor in the School.

Russell, Ph.D. student Raj Lal, and master's student Lina Luo worked with colleagues from the University of Minnesota, the Indian Institute of Technology, and Duke University. They found open burning of municipal solid waste accounts for 150 mg of fine particulate matter per square meter deposited on the Taj Mahal every year. The dung cakes account for 12 mg per square meter annually.

The team’s analysis also found the air pollution created from burning trash, primarily in poorer neighborhoods, leads to roughly 713 premature deaths in Agra, the city around the Taj Mahal. What’s more, the research said exposure to the pollution could have other health impacts that are more difficult to measure, such as acute reactions by visitors to the area.

Scaffolding surrounds a portion of the Taj Mahal undergoing cleaning to remove brownish discoloration from the white marble. School of Civil and Environmental Engineering researchers have found the cause of the browning in recent years: air pollution. Now a new study from Armistead "Ted" Russell and his colleagues pinpoints burning of household garbage in the surrounding community as a key source of that pollution. The fine particulate matter from all that burning also contributes to hundreds of premature deaths each year. (Photo: Michael Bergin) |

"Although it seems obvious, it perhaps takes an outsider to notice the significance of municipal solid waste burning that is happening all over Indian cities, and backing that hunch with field measurements and quantitative data does much to advance the science," Russell said.

The Times of India reported this is the first study to assess the direct impact of garbage burning on the iconic monument, though past studies have looked at better ways to manage solid waste in Agra.

Russell’s team noted those solutions have not been priorities because they didn’t appear to have significant impact on the discoloration of the Taj or public health. They said their new findings prove the opposite: developing better waste-management infrastructure can make a big difference.

"In Agra, the potential to spend less on cleaning up the Taj Mahal, improving health and improving visibility in the region are all great outcomes," Russell told Environmental Research Web. "One other benefit: if the trash gets picked up (the effective way to reduce trash burning in the city), you also don't have trash on the streets, making cities more livable."

Russell said his Minnesota colleagues are looking specifically at ways cities across India can deal with their trash.

"Their early explorations find that just decreeing a blanket ban on municipal solid waste-burning is not effective as people have no other options," Russell told the website. "Rather, finding new ways to serve underserved and poor neighborhoods with waste pick-up, and involving neighborhood associations in all neighborhoods appears to be promising."