The day after Christmas in 2004, a massive earthquake shook the ocean floor, sending a tsunami rippling through the Indian Ocean. When that surge reached the shore — from Thailand to Africa — it left more than 250,000 people missing or dead in 12 countries. Millions more lost their homes.

Hermann Fritz, a renowned tsunami expert in the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, did extensive research after the disaster, and he recently talked about the event a decade later. (Read more about how people in the affected areas remembered the anniversary.)

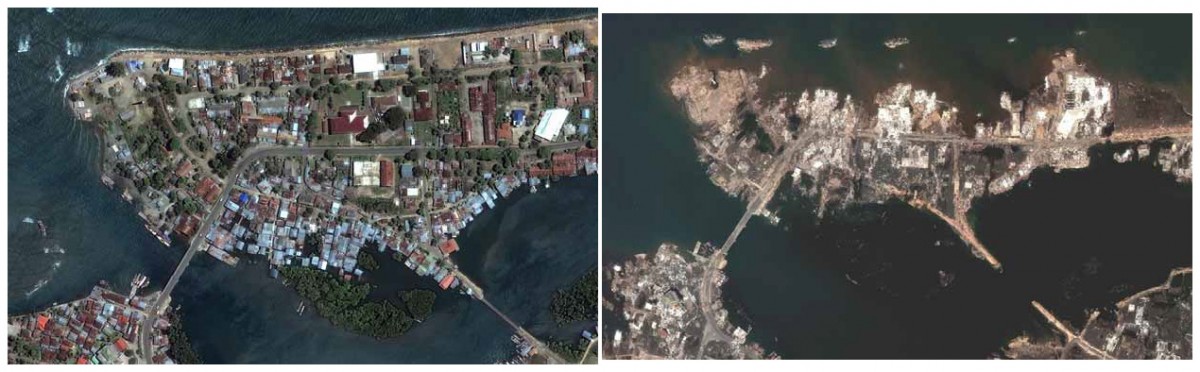

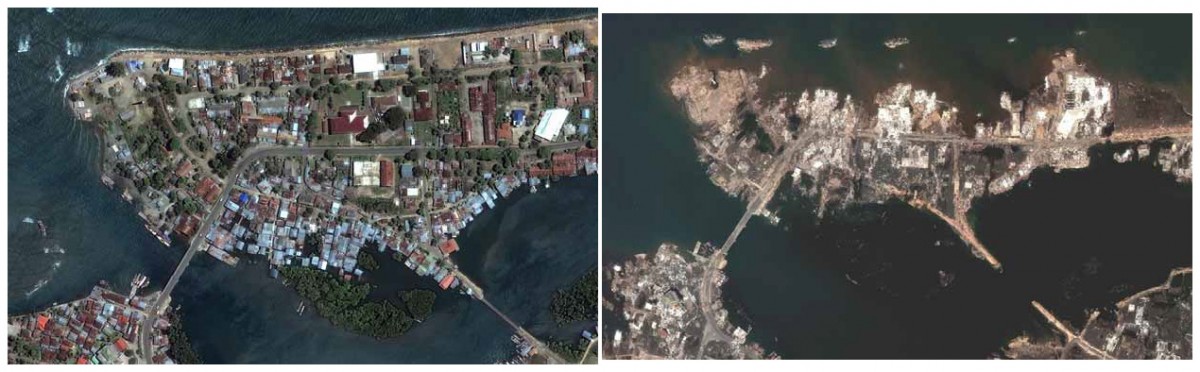

Banda Aceh City, Sumatra, Indonesia, shown in Digital Globe satellite images. On the right, before the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Afterward, on the left, much of the city is destroyed. The magnitude 9.0 earthquake that caused the massive tsunami occurred just off the coast of northern Sumatra.

|

Q:Where would you place the 2004 tsunami in the span of recorded events like this?

|

|

|

|

A:The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami is by far the deadliest tsunami in recorded history. There have, of course, been other mega-disasters over the past decade with death tolls exceeding 100,000 — Cyclone Nargis in 2008 in Myanmar (or Burma), the 2010 Haiti earthquake, or even farther back, the 1970 Cyclone Bhola in Bangladesh. All of these mega-disasters were amplified because they impacted very vulnerable and densely populated locations. All them occurred in the Indian Ocean.

What sets the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami apart is that it came as a grand surprise to the world population. While some scientists were speculating about the possibility of mega-thrust ruptures off Sumatra, the general public and the coastal residents were completely unaware of any potential tsunami hazard. The short time of just a few tens of minutes between the earthquake and the tsunami did not allow for any last-minute warnings, given the lack of an operating tsunami warning system in the Indian Ocean. Even seven to eight hours after the earthquake, some 300 people died in Somalia 5,000 km away. [Since then], warning system improvements primarily serve these distant communities that don’t feel the earthquake and may be completely surprised by an arriving tsunami.

It became a truly global disaster as the tsunami severely affected a dozen nations across the Indian Ocean, though the bulk of the death toll was on two densely populated Islands: Sumatra, Indonesia, and Sri Lanka. The largest media coverage likely came out of Thailand, where thousands of tourists from around the world, especially northern Europe, were trapped while enjoying warmer winter weather on paradise beaches.

And it was that media coverage, the eyewitness photos and videos, that gave the tsunami an image. Earlier magnitude 9+ events in the 1960s originated in remote and scarcely populated locations such as Alaska and Southern Chile, leaving behind only a few eyewitnesses and black-and-white photographs.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Kolhufushi Island, Meemu Atoll, Maldives, after a tsunami ricocheted around the Indian Ocean December 26, 2004. (All Photos Courtesy of Hermann Fritz.)

|

|

|

Q:Tell me about the work you did after the tsunami.

|

|

|

|

A: Up to 2004, my research was centered on tsunamis generated by landslides. Then, overnight phone calls with the leading tsunami pioneer, Professor Costas Synolakis from USC (University of Southern California) provided the opportunity to join and be trained by Costas, the leading expert, on my first international tsunami survey team in Sri Lanka a week after the tsunami. That was a colossal effort, with multiple survey teams orchestrated by Professor Phil Liu from Cornell.

Sri Lanka was, of course, already a disaster with an ongoing civil war. What stood out — apart from the Queen of the Sea rail disaster, the deadliest train wreck in human history — was how helpless people were just settling back in, right on top of the debris and wiped out villages. This is in stark contrast to the last U.S. mega-disaster, Hurricane Katrina, where residents were relocated and flood zones evacuated for months.

As a survey-team participant, my daily field work consisted primarily of interviewing eyewitnesses in the inundation zone and surveying water marks along profiles from the beach through the rubble and up to the inland inundation limit — fundamental information to understand the scale and onslaught of the tsunami, which provides critical data for tsunami model benchmarking.

Then calls for multiple subsequent field surveys followed: Sumatra, Indonesia, to analyze eyewitness video recordings; Maldives, Somalia, Oman, Madagascar, Comoros, Yemen. And then my last 2004 eyewitness-based data point was collected in Iran six years after the event.

|

|

|

An eyewitness interview in Sri Lanka:

"This man told us that he ran away with the tsunami breathing down his neck. Approaching a lagoon with crocodiles and with nowhere else to go anymore, he decided to climb this tree as a last resort — spontaneous vertical evacuation. We were skeptical about his story of survival at first, but then the guy said, “OK, I will show you.” And we reconstructed the running route, and he even climbed the tree where the tsunami rose to his ankles."

- Hermann Fritz, who spent years studying the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, which struck a dozen countries and killed 250,000 people.

|

|

Q:What did we learn from the tsunami and its aftermath?

|

|

|

|

A:The tsunami research community collected over 1,000 tsunami heights along the shores of the Indian Ocean, providing detailed runup heights and inundation limit distributions. The tourist photos from Thailand and tide gauge records highlight an initial draw down [of seawater as the tides retreat ahead of the arriving tsunami] on the overriding plate side of the fault rupture (in this case the east coast of the Indian Ocean basin). [When we see this, it] can serve as a last warning for evacuation. Unfortunately many tsunami unaware residents used the moment to collect fish stranded on the dry seafloor rather than evacuating.

The eyewitness video analysis at residential areas some two miles off the beach in Banda Aceh on Sumatra’s north tip showed that the tsunami approach may initially appear slow, but inundation speeds start to increase as the flow depth in the streets increases, trapping onlookers. In Sri Lanka, one of the main observations was that the tsunami impacted both the exposed east coast but also the densely populated west coast as the wave refracted around the south tip [of the island]. That led to bizarre scenes of phone calls from the flooded east coast warning west coast residents who did not understand the impending danger.

Then, in the Maldives, the surprise was that there were only 80 fatalities out of a population of 300,000 living at less than 2 m (7 feet) above sea level. Although entire islands were temporarily submerged by the overflowing tsunami, the deep channels separating the atolls allowed significant tsunami energy to be transmitted through the island chain without the massive runup effects observed on continental slopes like Somalia a few hours later.

[We also] learned that the impact [of these waves] is not uniform. In particular, underwater mountain ridges tend to focus the wave energy, which is what happened in Somalia along the Horn of Africa.

|

|

| |

| |

“One of the places I stayed in during the field work in Galle, Sri Lanka, was the ruins of a hotel flooded by the tsunami. Of course, the ‘hotel’ had no windows and was just a concrete framework. The rooms on the highest floor, the third floor, were partially usable as they were flooded only about 1 m deep. Nevertheless, when lying down to rest at night, I could see the mud line left by the tsunami on the walls of the room — above my head.”

A house in Sri Lanka left without most of its structure after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami that struck the day after Christmas.

|

Q:Would things be different if this happened this year instead of a decade ago?

|

|

|

|

A:Absolutely. Incredible progress has been made over the past decade with the installation of global tsunami warning systems and implementation of tsunami hazard zone mapping and evacuation and education programs. Perhaps most importantly since 2004, the word “tsunami” has become a household name. The tsunami warning systems will primarily serve populations at a regional distance and in the far field where the earthquake is not felt.

Ultimately, education and tsunami awareness are still most important in saving lives in areas close to the earthquake source, where the earthquake serves as the official warning and should trigger spontaneous self-evacuations if the earthquake lasts longer than 30 seconds. The 2011 Japan tsunami was broadcast on live TV as the inundation happened and evacuation orders were issued within minutes of the earthquake. Yet the best prepared Japanese population and society was still caught by surprise by the scale of the unexpected magnitude 9 event. Fortunately, 90 percent of residents of the flood zones survived in Japan despite the weaknesses revealed in the system. This kept the death toll in 2011 to 20,000, which is an order of magnitude smaller than in 2004.

With every event, improvements are made and lessons learned. This highlights how important it is to study these unique events in the field.

|

|

|

Q:Have you been back to the region? What’s it like now?

|

|

|

|

A:I have been back to some of the less-impacted regions of Indonesia and Oman. I have only seen photos from the hardest-hit areas over the years.

From other events in the Pacific, such as Japan and the Solomon Islands, I learned on return trips that nature comes back within a few years and dense vegetation takes hold again, masking the scars of the tsunami. Generally, indigenous populations —like those of the Solomon Islands who live in simple stick huts — are more resilient and bounce back rapidly, while more advanced societies with complex infrastructures — such as Japan — struggle longer with the reconstruction.

|

|

The mosque in Lhoknga, Indonesia, a town where 7,000 of the 8,000 resident died in the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. “The mosque sits half a mile off the beach [but] remained standing due to its well-built structure and open prayer halls that converted the building into a kind of pier during the tsunami,” said Hermann Fritz, who studied the disaster extensively in the years afterward. “Survivors climbed the roof as a spontaneous vertical evacuation platform. It barely remained dry.”

|

Q:How much do we still NOT know when it comes to these kinds of disasters?

|

|

|

|

A:The most fundamental thing still remains unsolved: nobody can predict an earthquake. So tsunami warnings only start in the minutes after the earthquake. Warning times have been reduced from tens of minutes to a few minutes after the earthquake. The fastest warning, in most cases, remains the earthquake itself for residents nearby. There are a few mysterious exceptions, such as slow earthquakes, which are highly [likely to cause a] tsunami but are barely felt by the coastal residents until the tsunami arrives.

Warnings have mostly been related to arrival times, but in the future, modeling progress will allow [scientists] to provide actual inundation forecasts in terms of flooding velocities and flow depths down to individual streets and neighborhoods. The actual seafloor deformation can still only be inferred through models. In the future, seafloor deformation measurements may provide more precise tsunami source characteristics. [Right now,] some surprising events, such as tsunamis generated by underwater landslides, remain difficult for early detection with existing seafloor instrumentation.

|

|