The accolades have come pretty fast and furious for Andy Phelps in recent months.

The accolades have come pretty fast and furious for Andy Phelps in recent months.

First, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) announced Phelps would receive a lifetime achievement award. Then, a few weeks later, the society elected him a fellow.

Now, Phelps is a guy who’s engaging and kind and full of life. But when he talks about the phone call telling him about his Outstanding Projects and Leaders Lifetime Achievement Award in Construction, well, his voice drops. And he gets very quiet.

“To be recognized by your peers, I thought, ‘How could this happen?’” Phelps said recently. “I love what I do, overseeing construction projects in remote places around the world. I don’t do it for some honor, but the fact that somebody saw that and considered me worthy for a lifetime achievement award — I was almost speechless.”

“I’m truly honored and humbled [to join] others who have received this and similar awards — people like Wally Baker of Hayward Baker and Associates, who was also an early mentor [of mine] in construction, and Steve Bechtel Jr., who received one of the first OPAL awards. To be added to that list is very humbling.”

A sampling of Phelps’ work, which his colleagues certainly judged to be worthy of such honor:

Andy Phelps, B.S. 1976, never got to drive the 1930 Model A Ford we all know as the Ramblin’ Wreck. He says (mostly jokingly) that is one of his biggest disappointments from his time at Georgia Tech. That’s not to say, however, that he didn’t drive a Model A at all. “I drove down [to Atlanta] in late August, and I’d given my primary car to my brother, whose car had died,” Phelps recalls. “I had restored a ‘31 Ford Model A. So I drove from D.C. down here in my Model A after completing a frame-off restoration. That was my only car at Georgia Tech, so it was a bit of a stand out. “I lived at the Kappa Sigma fraternity house. We entered my Model A with another fraternity brother’s classic car into the Ramblin’ Wreck Parade doing a gangster skit and won the classic car award two years in a row.” Phelps says he had fun at college, but he also worked hard. Had to, just to keep up. “Classes were hard, but a lot of the professors reached out and were mentors. If they saw you struggling, they pushed you. Dr. [Austin] Caseman knew I was struggling with my concrete course, and he pulled me aside. We sat down, and he showed me with just a little bit of emphasis how it really wasn’t that hard, and I got it.” Phelps’ two sons “got it,” too; Edward earned a bachelor’s, master’s and Ph.D. from Tech in biomedical engineering, and Michael has a B.S. in electrical engineering. Phelps say they all are “terribly proud of our Georgia Tech degrees, and they are serving us well.” “Both my boys are confident that no matter what the world throws at them, they can deliver. That’s something that you don’t get taught in the classroom but you sort of absorb it over the years you are here. And you build a confidence in your ability to go do things.” Phelps says he left Tech with a passion for engineering, but also for his alma mater. “I keep coming back because I think what this school does is different. I have been involved with other universities. But there’s something special here.” |

- He’s currently the principal vice president and global manager of operations for Bechtel Mining & Metals, overseeing projects throughout the world worth more than $20 billion.

- He coordinated Bechtel’s disaster recovery and relief efforts for many of his colleagues after the 2010 8.8 magnitude earthquake in Chile (a disaster that also destroyed his own apartment).

- He helped direct Mississippi’s response to Hurricane Katrina in 2005, housing more than 100,000 people in three months.

- He helped restructure and privatize the British nuclear energy industry in the early 2000s.

- He worked to evacuate Bechtel’s employees during the first Gulf War in the early ‘90s. Then he led Saudi Arabia’s efforts to stop, and clean up, a massive oil spill into the Persian Gulf caused by Iraqi forces under Saddam Hussein.

- He was a White House Fellow during George H. W. Bush’s administration.

Phelps — a 1976 graduate of the School of Civil and Environmental and a member of the School’s External Advisory Board — has any number of stories about the incredible and fun things he’s done in his career. But the one that might cut to the heart of who Andy Phelps is involves a village in eastern Peru and a young boy who wanted to go to school.

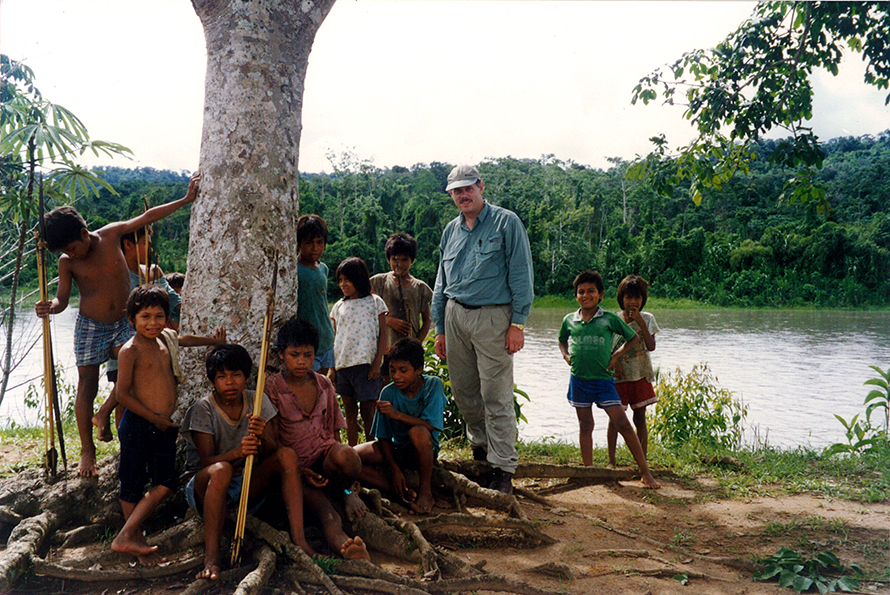

Phelps' traveling companions along the Urubamba River in Peru. (Photo Courtesy of Andy Phelps.) |

Phelps and three Peruvian women were traveling the Urubamba River through what’s called the Cloud Forest on the east side of the Andes Mountains. They were visiting the area of the Amazon basin inhabited by an indigenous people called the Machiguenga while they were doing siting studies for some plants Bechtel was preparing to build in the area.

One night, he’s eating in the chief’s hut and meeting some of the villagers.

“[The chief] brought a young man through and this young man talked about his schooling and how he couldn’t continue to afford to go to school. He would paddle his little canoe approximately a hundred kilometers away to go to the only school where he could gain a basic education. The young man asked if I would buy his father’s father’s bow and arrow so that he could afford to go to school.”

Phelps didn’t — it was against the rules because it could be considered by some as exploiting the indigenous people. But, after the boy left, he gave the chief a modest amount of money, a few hundred dollars. And he told the chief to use it to help the boy and others go to school.

“The next morning, we went to get in our boat to leave, and the village was empty. And there, lying in the boat, was that bow and arrow set. I looked at the people that were guiding me, and they said, ‘You can’t not take it.’ I said, ‘But it’s against the rules; we are not supposed to touch the culture.’ They said, ‘It would create a huge insult to not take it.’”

So Phelps took the bow and arrows, and his group set off down a tributary of the Urubamba, some 3,000 miles up the Amazon River.

“And as we turned the corner, the entire village was standing on this rock waiting to say thank you.”

Phelps and some of the children from the Machiguenga village he visited years ago east of the Andres Mountains in Peru in an area known as the Cloud Forest. (Photo Courtesy of Andy Phelps.) |

Now that ancient wooden bow and arrow set, with the permission of the Peruvian government, hangs on a wall in Phelps’ home along with mementos of every place he’s lived and worked — from Latin America to Canada, Europe to the Middle East.

It’s emblematic of the work Phelps said he’s always tried to do as a civil engineer. He was looking for places to build facilities to extract valuable natural resources in the area where the Machiguenga live in a sustainable way that respected the indigenous tribe.

“How do you make sure what you’re doing you feel proud of and hasn’t left a scar or hurt people?” Phelps said. “Because what we should be doing is like doctors: cause no harm.”

“Why do we do civil engineering? Why did I choose it? It’s about helping the world and helping people live better,” Phelps said. “I love that part of it.

“Why do we build a road? Why do we build a sewage treatment plant? Why do we build a copper smelter? It’s because the people like that young boy in the jungle, when you ask what they want out of life, go to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: they want safety and security. They want shelter, they want food, they want an opportunity to succeed and become educated, they want a chance to become someone better and stronger. That’s human nature. So what we do in civil engineering allows people to realize their full potential.”