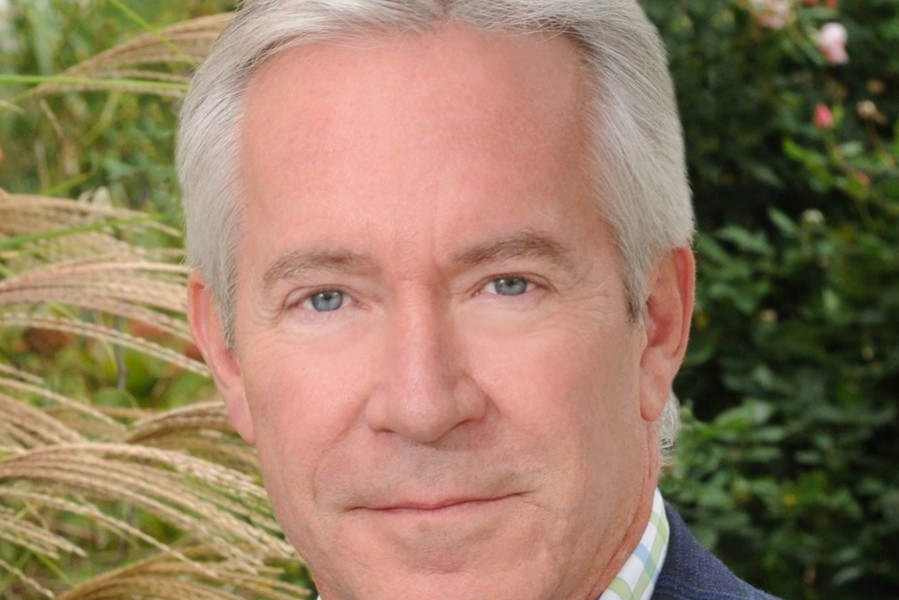

To his customers and colleagues, Bill Higginbotham is CEO of ET Environmental, an Atlanta-based design-build-construction company with offices in 13 states. But when asked to state his profession, Higginbotham has a one-word answer.

“Engineer,” says the 1976 GT-CEE graduate. “That’s the basis for everything I’ve been able to do.”

That’s saying a lot.

Higginbotham’s business savvy alone would put many MBA’s to shame. He opened the doors to his first business, Chattahoochee Geotechnical Consultants at age 29 and negotiated a merger with EMCON a decade later. A subsequent joint venture with Turner Construction brought him to his current incarnation, as the head of ET Environmental, a $100-million firm that provides construction, design and environmental services to individual businesses and government agencies.These days, business is good, but Higginbotham takes nothing for granted. He’s enjoyed good times and weathered bad ones. Through it all, he’s learned that success is a moving target - a lesson that was drummed into him at Georgia Tech.

|

| Bill Higginbotham, 1975 Courtesy of The Blueprint |

“When I was in high school, I was in the National Honor Society and had good grades. But I didn’t really lift a finger to work hard. I thought that in college, I’d be able to read the book, drink a beer, and pass the test,” he said with a dry smile. “But at Georgia Tech it didn’t work that way.”

That doesn’t mean Bill Higginbotham didn’t try to make it work that way, however.

As a freshman Higginbotham looked for what appeared to be “the most vaguely defined engineering major” the school offered, thinking he would be able to slide by with minimal effort. Appearances deceived him. That vaguely defined major – engineering science and mechanics –promptly kicked his butt.

“I didn’t have the study habits or the work ethic that Tech demands, and it was killing me,” he said. “The kids who had worked hard in high school, studying four or five hours a night, they were just doing what they had been doing for years. They were doing fine. I think I set a record for the most number of academic probations for a student who actually graduated.”

|

| Bill Higginbotham, 2013 |

That he graduated – on the Dean’s List – is a testimony to what Higginbotham refers to as the “boot camp mentality” that prevailed at Georgia Tech. Professors were helpful, even inspiring, but it was up to Higginbotham to develop a work ethic and stick with it. He refers to this process as “grinding it out” and, as the phrase implies, it wasn’t always pleasant.

“The attitude at Tech was ‘get it or go home.’ There weren’t any tutors trying to help you do what you could do yourself,” he said.

“It was a mental toughness that has taught me more about business success than anything else before or since. Sometimes in business, you need to just grind it out.”

By the time he was a junior, Higginbotham had discovered something that made all of that grinding worthwhile: civil engineering.

“I was interested in saving the planet – environmental engineering— so I was advised to take a sanitary engineering class. When I got in there, I actually understood what they were talking about,” he said.

“The tangibility of civil – bridges, roads, clean water – these things made it easier to grasp the underlying mathematics and physics. That’s when I stopped worrying about failing classes and started working hard to understand the material.”

|

| Bill Higginbotham in the Atlanta headquarters of his company, ET Environmental |

It’s also when he started to trust that there was a method to the madness of higher education. Suddenly, foundational classes like calculus seemed less of a chore and more of a means to an end.

“If you are trying to understand almost any natural process, there’s a series of equations that can help you model it,” he said. ”I’d never s understood that before, but when I did, it changed everything.”

But it didn’t make it less of a grind.

Higginbotham is reminded of this fact when he talks about a recent donation he made to the Mason Building. As a result of that donation, his name is now emblazoned on a plaque in the third-floor hallway.

“The professor who taught Structures worked me very hard. It’s only fitting that that professor will have to see my name every time he goes down that hall.”