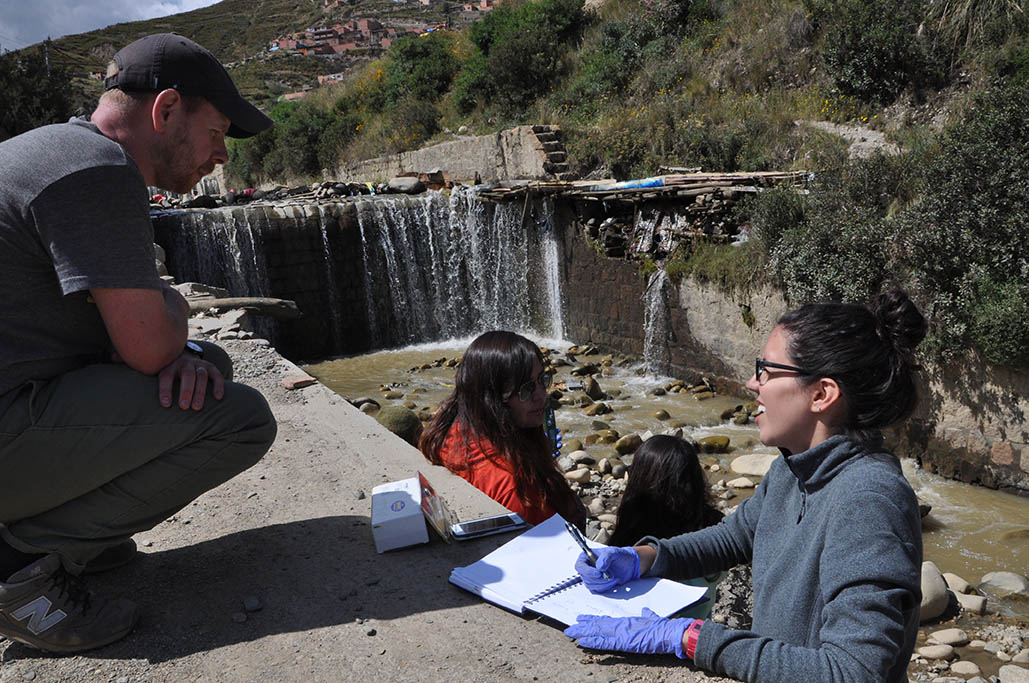

Assistant Professor Joe Brown has won an Early Career Development Award from the National Science Foundation. These so-called CAREER grants recognize promising young faculty with funds to help them build the foundation for a lifetime of study and expertise. Brown will study microbial interactions at the interface of air and water, searching for evidence that dangerous pathogens can become airborne in developing countries with poor urban sanitation systems. (Photo: Jess Hunt-Ralston) |

When Joe Brown went to India last summer, he was hoping to collect samples that could help answer some questions he’d been thinking about for a while.

His years studying sanitation and global health had given him the idea that the open sewers and overflowing latrines common in the dense cities of the developing world could be linked with disease through an unusual mechanism: airborne transmission of pathogens.

In other words, it’s not just the well-documented connection between unsafe water, poor hygiene, or direct contact with sewage that leads to poor health in communities lacking effective sanitation. It could also be that pathogens are flying through the air.

What he found along the Ganges River and next to open sewers in Kanpur, India, confirmed it was an idea worth pursuing.

|

“We found aerosolized Giardia, we found aerosolized Salmonella, Shigella, enterotoxigenic E. coli,” Brown said, “all kinds of things that we weren’t sure were transmissible in aerosols. These are some of the most important pathogens affecting health in low-income communities.”

Now he wants to expand the work, and the National Science Foundation has given him the resources to do it with an Early Career Development award.

Known as CAREER awards, these five-year grants are NSF’s most-prestigious award for early career faculty. They identify potential leaders and academic role models, giving them funds to build the foundation for a lifetime of study. Brown learned he’d received one in January.

“I’m thrilled. This award offers substantial support for doing something really innovative, moving into a new area that’s well-connected to my previous work but which stands alone as a very uncharacterized area that’s in need of primary research,” Brown said. “I see it as a great opportunity to build on what I’ve already done and to generate new knowledge.”

In some ways, Brown said, the work he’s proposing is uncharted territory. He’ll combine two areas of research that haven’t come together much.

“I’m really interested in microbial risks at the interface between air and water,” he said. “Scientists studying air quality don’t generally know much about pathogenic microbes, especially those associated with water and sanitation. Others studying environmental health microbiology [typically] study waterborne transmission; they don’t know much about bioaerosols. Those communities don’t intersect very often.”

Joe Brown and undergrad Valeria Hernandez discuss some of the field samples the students collected in Bolivia in 2016. The group traveled as part of Brown’s Environmental Technology in the Developing World course. Some of the work they did served as pilot data for Brown’s newly funded Early Career Development award from the National Science Foundation. (Photo Courtesy: Environmental Technology in the Developing World Class) |

Brown wants to study three cities in the developing world: Kanpur, Phnom Penh in Cambodia, and La Paz in Bolivia — three places where he’s worked, where he has connections and collaborators, and where poor sanitation is the norm. Think open sewers flowing with a mixture of human waste, trash, storm water, and industrial discharge.

That means lots of people live in close proximity to waste that’s often teeming with nasty pathogens, a problem exacerbated because many infectious diseases already circulate in these communities.

Brown said researchers have documented pathogens becoming airborne indoors in economically advanced countries — for instance, in bathrooms where showerheads or flushing toilets can aerosolize microbes — or around wastewater treatment plants. Yet very little work has been done on potential exposure via air in the large, highly contaminated cities of the developing world.

Brown aims to find out if those open sewers and overflowing latrines are allowing dangerous pathogens to become airborne and increasing the risk of people getting sick.

“Right now, we’re just trying to understand, are there pathogens there? Are they viable? Do they contribute to enteric disease risks? The fundamental work we propose will help us better understand whether sanitation-related bioaerosols are an important pathway for exposure in urban environments.”

Brown also has preliminary data from La Paz, thanks to undergraduate students in his Environmental Technology in the Developing World course. Future students in that class will play a major role in the research.

“My goal here is to provide global learning opportunities for undergrads in engineering. That’s something a lot of our students are interested in,” Brown said. “That’s what the educational component to this grant is explicitly about: getting undergrad researchers out in the field, having them involved in data collection, getting them to see something different, and bringing engineering fundamentals to those big-picture questions around global health.”

Filling in a bit more of that picture is a big part of what Brown said he’s trying to do with this project.

“You have these interconnected problems of wastewater, storm water, and solid waste, which make open sewers the de facto reality for much of the developing world,” he said. “If this study or other studies like it end up finding that existing infrastructure isn’t very effective at reducing sanitary risks — which, we may well find that — there’s no easy solution there. We are decades away, at least, from safely managed sanitation in cities across the developing world. And the pace of urbanization is increasing.

“I look forward to expanding our understanding of urban sanitation, and that includes pursuing complex problems that lack easy answers.”