Floodwaters cover Port Arthur, Texas, on August 31, 2017, following Hurricane Harvey. Staff Sgt. Daniel J. Martinez took this photo from a South Carolina Helicopter Aquatic Rescue Team UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter during rescue operations following the storm. (Photo: Staff Sgt. Daniel J. Martinez, U.S. Air National Guard) |

When Hurricane Harvey flooded Houston last year, many residents turned to social media to cry out for help.

Sometimes, with emergency lines jammed, that was the only way to communicate.

Other people stopped posting altogether — perhaps because they were saving the last of their phone’s battery or were too busy trying to evacuate after the storm.

Meanwhile, hundreds of residents from neighboring Louisiana motored west to help, bringing boats and bodies to supplement emergency crews.

With another hurricane season beginning June 1 — and some forecasters predicting another busy one — researchers in the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering are working on a tool to help first-responders use Twitter activity to identify developing crises after a storm while also helping civilians more effectively plug in to disaster response efforts. It’s the result of a grant from the National Science Foundation, which was looking for ways to learn from Harvey.

Led by Frederick Law Olmsted Professor John E. Taylor, one of the interesting results of the team’s work over the last year was that a lack of activity can be just as instructive as people asking for help.

“Obviously, where people who are in trouble have explicitly said, ‘I'm in trouble,’ that's critical to respond to,” Taylor said. “But an important secondary predictor is, what about areas where people are saying nothing where they were before?”

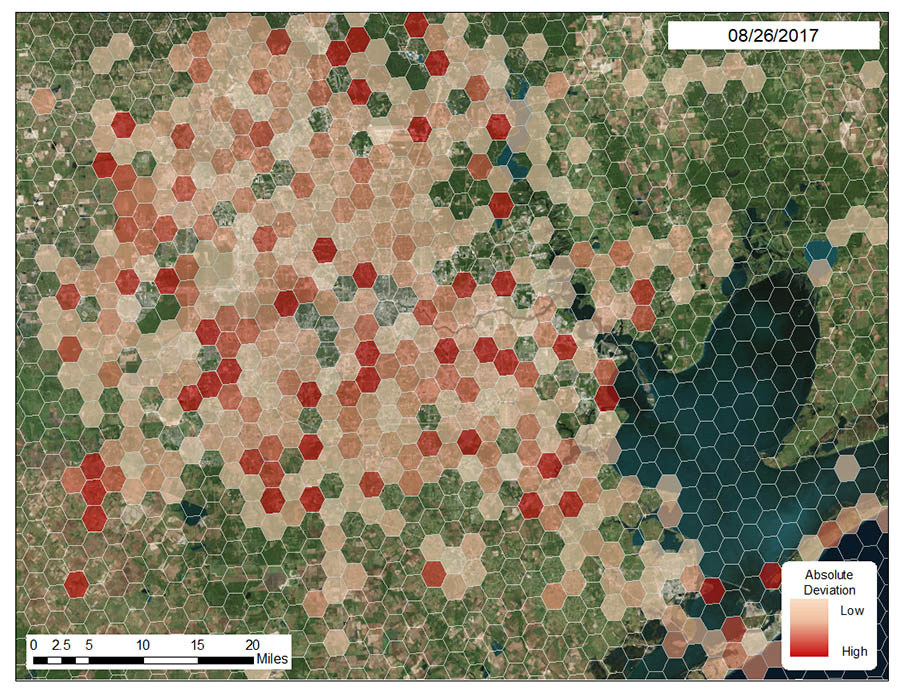

A hexagon grid overlaying Houston shows the reductions in Twitter activity the day following Hurricane Harvey's landfall in August 2017, with darker red hexagons high levels of deviation. Ph.D student Rachel Samuels is working with John E. Taylor on a National Science Foundation project to use Twitter activity to help first-responders identify developing crises after a storm while also helping civilians more effectively plug in to disaster response efforts. (Image Courtesy: Rachel Samuels) |

“How do we hear the silence?” asked Taylor’s Ph.D. student Rachel Samuels, who presented the work at a big disaster conference this week. “How do we turn silence into sound?”

Samuels collected building-level damage assessments from the Federal Emergency Management Agency and compared that to the Twitter activity, breaking the city into 10-kilometer areas. Her idea was to map real-time damage using tweets.

Using posts on the micro-blogging site has been done before by researchers who match spikes of activity to infrastructure damage, Samuels said.

“What we found that it missed are these data shadows, where areas that don't have any Twitter activity at all are also being damaged. So, how can we shed some light on those data shadows?”

That’s where the team’s new software tool will come in. Using tweets from users that have tagged their posts with their location, their system can assess the sentiments people express, identify trending topics in localized areas, and also note where activity has dropped off significantly from normal — all in the service of helping emergency workers better identify where they need to deploy their resources.

“We're using unsupervised machine learning techniques to extract what we call ‘geo topics,’” Taylor said. “A topic that is associated with negativity that's in a certain geographic space comes to the list, and the first responders will see a list of, for example, the five leading geo topics that are occurring right now somewhere in the city.”

Uniquely, users don’t have to tell the system anything about what to look for — a key advance, Taylor said.

“That is actually the key innovation to the backend system. You don't have to, a priori, know what you're looking for.”

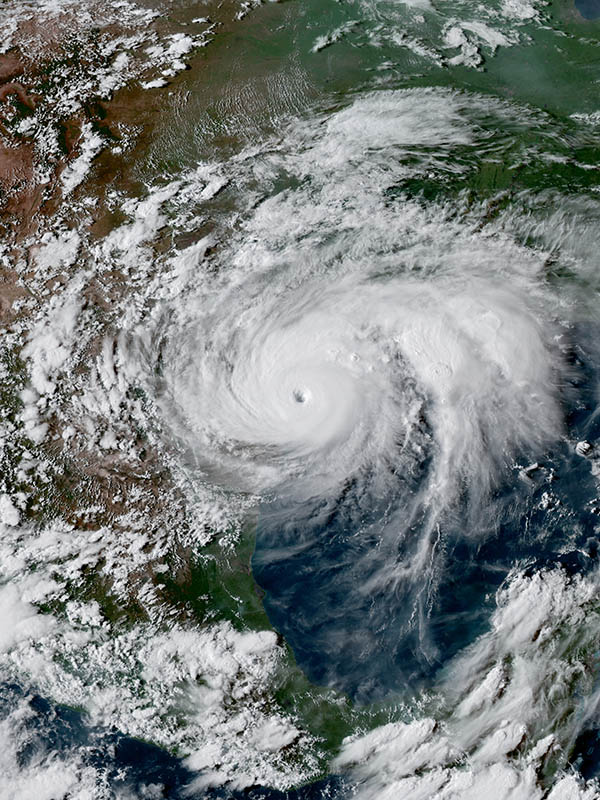

Hurricane Harvey churns near the coast of Texas at peak intensity late on August 25, 2017. (Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) |

The backend programming for the system is operational, thanks to the work of Taylor’s now-graduated Ph.D. student Yan Wang, but Samuels is still working on the front-end design for the software. Taylor said they plan to meet with five to 10 emergency response agencies throughout the summer to collect feedback and improve the system. But they also hope to offer a beta version of the system to responders so they can use it this hurricane season.

There’s one other piece to the software that Samuels is especially excited about: the ability to link professional disaster responders and people who just want to help coordinate their efforts. That grew out of Samuels’ respect for that Cajun Navy that cruised from Baton Rouge to Houston last August to help people in need and the Cajun Army that put boots on the ground after floodwaters receded.

“Part of why I really wanted to do this was to also provide a platform with which citizen responders, who I would really like to be able to enable, can also work with emergency response professionals,” she said.

“I'm very impressed with the Cajun Army. I would love to be able to make it easier for them to also be able to coordinate with the people whose job it is to respond to these disasters.”

Taylor said the system will be useful for large disasters other than hurricanes, too, like an earthquake, where problems develop in the immediate aftermath of the initial event.

“This is about identifying smaller crises happening within a much larger crisis. There are dangers within this larger, monolithic thing like an earthquake or a hurricane. We need to take advantage of emerging data streams to find those in danger and get help to where help is needed.”