|

Rose Dhu Island is home to the Girl Scouts' Camp Low. The group is also considering building an "eco-village" on the island that would use electricity generated by the tidal flows off the island's shores. Kevin Haas and his team are developing a tidal turbine to generate that power. (Photo Courtesy of Kevin Haas. Map via Google Maps.) |

|

The Girl Scouts are considering building an “eco-village” on the island they own along Georgia’s coast, and they want to harness the ebb and flow of the tide to power it.

The camp would be a place for young girls to learn about sustainability and green energy, and as part of that, the organization wants it to be completely self-sustaining.

They’ve turned to Kevin Haas to help. Haas studies tidal energy and is an associate professor in the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering. His research group is developing a turbine that could be placed just off the banks of Rose Dhu Island in the Little Ogeechee River, generating enough power for the Girl Scouts’ camp.

“Anywhere you have flow constrictions — places where you’re funneling tidal flow through a narrow opening, you’re squeezing the flow — velocities increase, so you get much more kinetic energy,” Haas said. “What we want to do is use tidal turbines that will generate electricity in those hot spots of high velocity concentration.”

Haas’ work has promise far beyond coastal Georgia, where the Girl Scouts’ eco-village could be an early beneficiary. Tidal power could be a game-changer for remote villages such as those found in Alaska. Many rely on diesel fuel that must be flown in, driving energy costs to four or five times what many residents of the lower 48 states typically pay. Small tidal turbines could offer an alternative energy source in these areas.

For coastal residents in the continental United States, small-scale turbines could supply power for lights and boat lifts on docks, eliminating the hassle and expense of running power lines to the end of the piers.

They also might one day help power some of the nation’s Navy or Coast Guard bases, which are working to become self-sustaining.

Haas has assessed the potential for tidal energy across the entire country for the U.S. Department of Energy. He said much of the development so far has focused on commercial-scale projects to generate significant power. Yet, much of this untapped resource could offer a supplemental power source to small coastal communities.

So his research looks at the shallow, narrow coastal estuaries where utility-scale turbines won’t work, but where currents flow fast enough to produce modest amounts of electricity.

That’s where the Girl Scouts project fits in.

“This river’s about 500 meters wide. Our biggest depth where we’re looking is about 10 meters. There’s quite a bit of recreational boat traffic in the area, so you have to get down below that. The size of your turbines is quite limited, but the required power is not huge—we’re talking a couple of kilowatts,” Haas said.

|

|

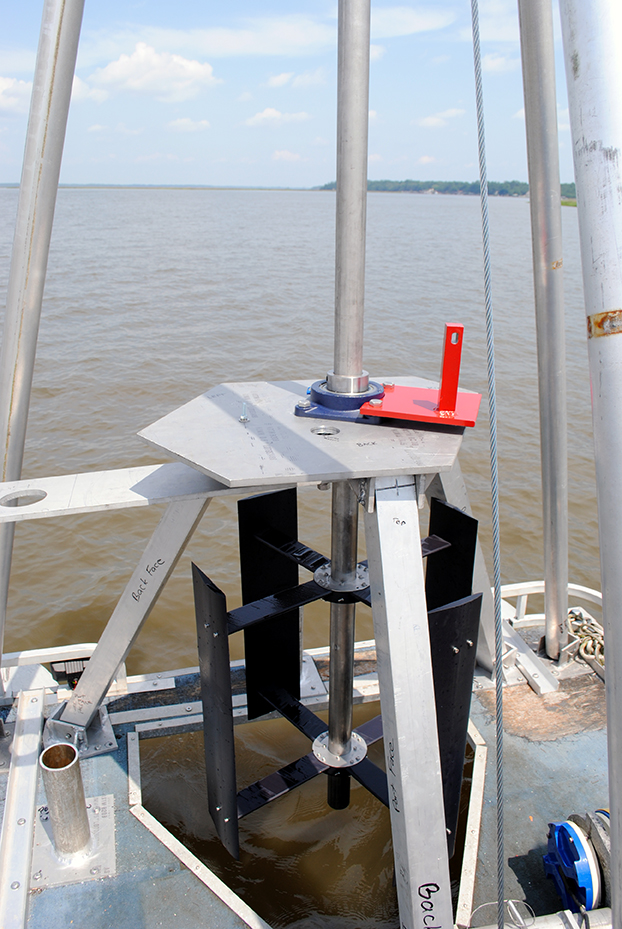

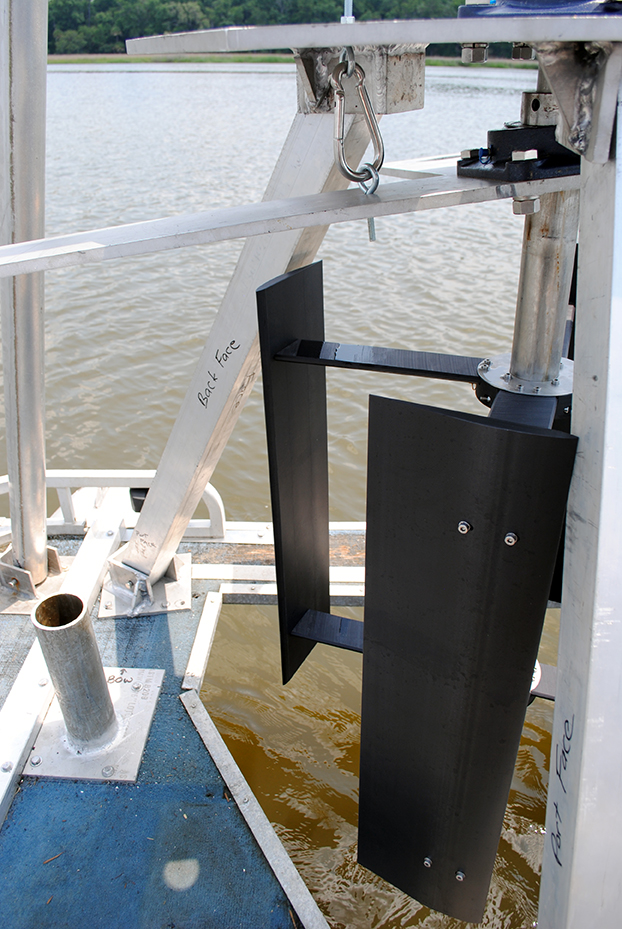

| The rotor and testing rig Kevin Haas and his team attached to their research boat. They spent part of the summer assessing how well the rotor turns as tides ebb and flow in the Little Ogeechee River along Georgia's coast. (Watch a video of the test.) They're trying to find the best design — and the best location in the river — so they can turn the tides into modest amounts of electricity. (Photos Courtesy of Kevin Haas.) | |

With the support of the Ray C. Anderson Foundation and through a collaboration with Cardiff University’s Thorsten Stoesser, a former CEE faculty member, Haas and his team have been trolling the waters near the island this summer testing a rotor designed to rotate as water surges into and flows out of the river. It’s detailed, time-consuming and complicated work, thanks to a channel that curves and splits into two different rivers. And some of the water floods nearby marshes, also altering how currents move around the area.

Haas |

|

“We want to understand all of these different processes to help decide, where do you put the turbine? How do you design your optimal place?” Haas said. “You can’t just say, well, I’m going to put it where the strongest currents are. The strongest currents migrate.”

“Trying to design what’s going to give me the best overall power, that requires a very detailed understanding of how the currents vary.”

The next step for Haas’ team includes field testing the full turbine with a generator that will create electrical power from the mechanical power of the spinning rotor. He’s working on those designs with Stoesser who is also the technical director for Repetitive Energy Company, a startup developing the tidal turbine. Prior to field testing, they plan to run full system tests later this fall using an on-demand whitewater facility in Cardiff.

“Tidal [energy is] going to be part of the renewable portfolio,” Haas said. “It is definitely not the only answer, [but] it has the potential to help a lot of communities.”