A new study led by Tellepsen Chair Armistead "Ted" Russell found that power plant and motor vehicle pollution regulations resulted in better air quality and fewer emergency hospital visits for Atlanta area residents for respiratory problems. His team's analysis looked at actual conditions from 1999 to 2013 and compared them to the expected conditions had six different sets of regulations not been enacted. In some cases, emergency room visits dropped by double-digit percentages. (Photo Courtesy: Nick Humphries via Flickr.) |

Russell |

|

MORE ABOUT THE STUDY |

By Health Effects Institute

Do air pollution control measures actually work?

A new rigorous study published April 19 by the Health Effects Institute says yes.

After a number of national and state air pollution control measures taken in and around Atlanta, Georgia, Armistead “Ted” Russell and colleagues from the Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University examined whether such regulations targeting power plants and mobile sources were effective in reducing pollutant emissions, improving air quality, and ultimately improving health.

Their comprehensive report, Impacts of Regulations on Air Quality and Emergency Department Visits in the Atlanta Metropolitan Area, 1999–2013, finds that air quality actually improved substantially — and fewer people visited hospital emergency departments as a result.

Although it is assumed that air quality actions, once adopted, will improve air quality and health, there are few studies that actually test that. This new study is the latest in a series of studies in HEI’s Accountability Research program, which systematically test whether actions intended to improve air quality and health actually produce that effect.

“The atmosphere is very complex, and we were able to use our research tools developed for atmospheric science and engineering studies to help answer pressing public health questions,” said Russell, the Howard T. Tellepsen Chair and a Regents professor in the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering. “The result was a one-of-its kind analysis showing the effectiveness of specific regulations at each step of the process.”

Using an innovative approach, Russell and his colleagues compared the actual conditions from 1999 to 2013 with carefully estimated quantitative projections of emissions, air quality, and emergency department visits that likely would have occurred in the absence of six national and state level regulatory programs.

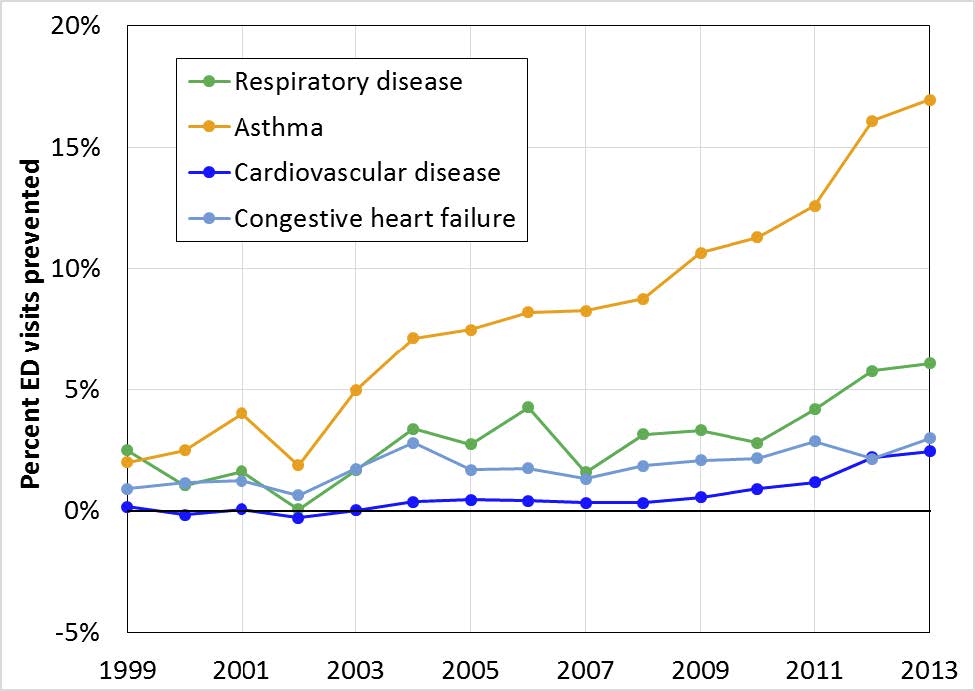

This graph shows an estimate of percentage reduction in emergency department (ED) visits from pollution control policies in the five-county metro Atlanta area between 1999 and 2013. The graph shows the reduction compared to the number of visits researchers would have expected without the pollution controls. (Courtesy: Health Effects Institute)

This graph shows an estimate of percentage reduction in emergency department (ED) visits from pollution control policies in the five-county metro Atlanta area between 1999 and 2013. The graph shows the reduction compared to the number of visits researchers would have expected without the pollution controls. (Courtesy: Health Effects Institute)

|

The investigators found that air pollutant emissions and ambient concentrations decreased over the study period for most pollutants and estimated that the pollutant levels were lower than what would have been expected without regulatory actions (a “counterfactual” scenario).

Their analysis also found that the observed improvements in air quality were associated with fewer emergency department visits for asthma and other respiratory disease compared with what would have been expected without the regulations. And their data suggested that the benefits increased over time as the air pollution control measures were fully implemented and emissions went down.

“One of the real strengths of this study was that it truly combined the engineering expertise at Georgia Tech with the public health expertise at Emory to do a very detailed accounting of how regulations impact air quality and health,” Russell said.

In its independent review of the report, the HEI Review Committee noted that the study was an ambitious application of the organization's accountability framework as it encompassed a broad suite of regulatory programs designed to reduce multipollutant emissions from power plants and mobile sources in Georgia and nearby states.

“This was an extraordinarily careful analysis of just what happened in Atlanta after these many, complex actions were taken,” said Dan Greenbaum, HEI’s President. “And the good news is that all of the effort put in by government and the private sector appears to have paid off in cleaner air and better health.”